What is The Way of Archery (射道) ?

The term "The Way of Archery" is the English translation of 射道 (pronounced she dao in Mandarin Chinese). Gao Ying (高穎) was the Ming Dynasty author of the early 17th century military archery manuals, An Orthodox Introduction to Martial Archery (Wujing Shexue Rumen Zhengzong 武經射學入門正宗) and An Orthodox Guide to Martial Archery (Wujing Shexue Zhengzong Zhimiji 武經射學正宗指迷集) upon which we based our translation and commentary for our book. Gao frequently referred to The Way of Archery (written as 射之道 in his work) to describe both a Chinese technique and philosophy for archery.

Links and Contact

Feel free to send an email Jie Tian and Justin Ma at thewayofarchery@gmail.com about

- book orders

- rates and scheduling for private lessons and online coaching

- historical Asiatic archery demonstrations and consultations for films

- running training programs for your team building activity

Please subscribe to The Way of Archery - YouTube Channel to stay up to date on our latest videos.

Please visit the The Way of Archery - Facebook Page for occasional book snippets and posting about our activities.

Please visit the Chinese Archery - Facebook Group for general discussions about Chinese Archery.

The Way of Archery focuses on the technique side of archery. If you are interested in acquiring equipment (bows, quivers, thumb rings) for shooting in the Chinese or Asiatic style, please visit The Cinnabar Bow.

Philosophy

The Way of Archery is a process of continual self-improvement. You must practice diligently, whether outdoors or in front of the gaozhen (written 藁砧, a bale placed at very close range for form tuning practice). You scrutinize every element of your technique so that you can eventually develop your form into a cohesive, intuitive whole. Whenever possible, you should practice with like-minded friends, being open-minded and receptive to their good advice.

Every mistake is a learning opportunity, whether you miss the mark, whether your arrow wobbles visibly (despite hitting the mark), or whether you feel unexpected pain in your joints and tendons. You must take a step back to patiently assess your problem and fix it. All the while, you must be honest with yourself, because the arrow and your body will not lie to you.

Archery, at its core, is very simple: look at the target, draw the bow straight back, release the arrow in a straight line, and do so comfortably. But the path to understanding and appreciating that simplicity is a deep, neverending journey towards refinement. As such, once you step on The Way, it will bring you a lifetime of enjoyment.

Confucian philosophical roots of Chinese Archery

Wang Yangming (1472--1529, born in Yuyao, Zhejiang) was a pillar of Chinese philosophy during the Ming dynasty. During his life as a statesman, general, and philosopher, he accomplished great feats despite the often harsh environmental (and political) circumstances he faced. Because of his life experience, he came to rediscover the original meaning behind Confucian philosophy: as a system of ethics and self-improvement that would lead to developing a resilient (yet poised) mindset to face the rigors of life. His work would go on to influence important thinkers in China and Japan in the subsequent centuries.

Wang was an avid practitioner of archery as well, as archery was the most highly regarded martial practice in the Confucian system. The following is a passage with his reflections on archery as a means for observing virtue:

"A Note on Observing Virtue" by Wang Yangming (Ming Dynasty)

When the gentleman is practicing archery, his inner will must be correct, his outer body must be straight, and his handling of the bow and arrow must be focused and solid. Only then can he talk about hitting the target. That is why the ancients used archery to observe virtue.

Virtue: you obtain it from your heart.

A gentleman’s learning is directed towards seeking virtue from the heart.

Thus, when a gentleman practices archery, it is to preserve his heart.That is why with impatience in his heart, his movements are reckless.

With wander in his heart, his vision is superficial.

With regret in his heart, his breath is starved.

With negligence in his heart, his appearance is lazy.

With arrogance in his heart, his expression is conceited.

These five things do not preserve the heart. Those who cannot preserve their heart are not learning.When the gentleman learns archery, it is to preserve his heart.

That is why if his heart is upright, then his body will be correct.

If his heart has respect, then his expression will be serious.

If his heart is peaceful, then his breath will be comfortable.

If his heart is concentrated, then his vision will be focused.

If his heart is coherent, then he will be timely and principled.

If his heart is clear, then he will be deferential and respectful.

If his heart is grand, he wins but is not overzealous, he loses but is not deflated.

With these seven things in order, the gentleman’s virtue will be complete.The gentleman will always find utility in their study, and through archery we can see [the results of that effort]!

That is why they said:

For the lord, being a good lord is his target.

For the vassal, being a good vassal is his target.

For the father, being a good father is his target.

For the son, being a good son is his target.In archery, you shoot for your personal target. The target: your heart.

Each person shoots for their own heart. Each is obtaining their heart alone. That is why they say “you can observe virtue”!

History and Culture

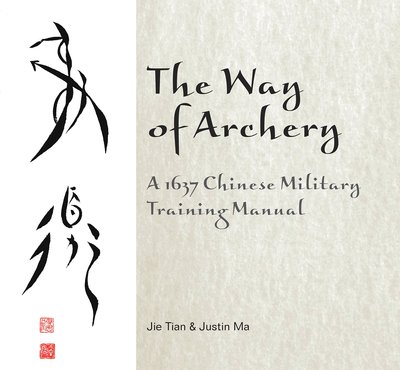

The calligraphy for 射道 (she dao) on the front cover of our book was painted by Zhang Chen (章晨 先生), member of the Chinese Calligraphers’ Association (中國書法家協會會員). It is written in the style of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BC) bronze script (金文). As this is an earlier style of writing, we can see the character for “archery/shooting” (射) resembles an archer shooting an arrow from a bow. The ancient character for “way” (道) shows people (人) on the left and right walking on the path towards the truth as a destination (首) – this is how a path becomes a way. These two words written in bronze script are a testament to the importance archery has played in Chinese culture at least 3,000 years ago and even earlier.